I just got a suggestion to write about the putative link between the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism. I'm happy to oblige, as this is a subject that connects to science, public health, public perceptions of science and medicine, all things I find very interesting! This is a fairly long post, so quick summary: the MMR-autism link is bogus; the uncertainty that the MMR-autism claim has created has led to concrete harms in terms of public health; and the widespread acceptance of the claim is typical of modern skepticism about the "scientific establishment." Feel free to skip down to whichever section interests you most.

MMR vaccine does not cause autism

In 1998, a group of doctors led by Andrew Wakefield published a

paper associating the MMR vaccine, gastrointestinal inflammation, and autism in a study of 12 children. The paper stated that in these children, intestinal inflammation and "neuropsychiatric dysfunction" (diagnosed as autism in 8 of the 12) followed MMR vaccination, usually within a week. Even though they were cautious enough to state that "We did not prove an association between measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and the syndrome described," public fears of the MMR vaccine became widespread and MMR infant vaccination rates

fell to record lows.

As it turns out, Andrew Wakefield received £55,000 (over US$100,000 at current exchange rates) from lawyers who were suing the manufacturers of the MMR vaccine. He found his patients through those lawyers, whose clients were the parents of many of the children in the study. He never disclosed this conflict of interest. 10 of the 13 original authors

retracted the study when they found out. What's more, the study represents a few children that Wakefield selected precisely because of a temporal coincidence between MMR and autism (i.e., which caused parents to worry and join a lawsuit. This selection bias is a fatal flaw on top of the failure to disclose a critical conflict of interest.

As for methodologically valid studies:

this one found that incidence of autism is equal among MMR-vaccinated and non-MMR-vaccinated children (498 autistic children analyzed from a survey of medical records). Incidence of autism in the UK steadily increased from 1988-1993

even though MMR vaccination rates were virtually constant at 95%.

Within autistic children, neither "developmental regression" (meaning worsening of symptoms) nor bowel problems increased from 1979 to 1999. (The MMR vaccine was introduced in Britain in 1988

after a measles outbreak killed 17 people.)

This study, covering 5773 people, also found no evidence for a link between MMR vaccine and autism.

Anti-vaccine movements lead to concrete harms

MMR infant vaccination rates in Britain are now about

80%. Before the 1998 MMR scare, vaccination rates approached

92%. 95% coverage is required for "herd immunity" to kick in, where so many people are immune to measles, mumps, and rubella that the viruses cannot spread in the country at all.

Before the MMR vaccine was introduced in 1988, a handful of children died of measles in the UK every year, and thousands contracted it. (The death rate from measles is pretty low for healthy children.) After 1992, there has not been a single death from measles in the UK. (

Worldwide, it's estimated that almost 800,000 people died from measles in 2000, out of almost 40 million people who got the disease, mostly in Africa and Southeast Asia.)

But now, the percentage of unvaccinated children is high enough that measles is

on the verge of becoming an endemic disease in the UK. In technical terms, the "reproductive number" (R) of the measles virus, or the chance that each infected person will transmit the virus to another uninfected person, rose sharply from 0.47 to 0.82 from 1995-98 to 1999-2002. Above R = 1.0, the disease is endemic (e.g., common cold); below 1, it occurs in isolated outbreaks. If reduced vaccination rates continue, the proportion of unvaccinated children will grow (after all, 1998 was only 6 years ago), and R will grow as well. I quote the original

Science paper:

If the current low level of MMR vaccine uptake persists in the UK population, the increasing number of unvaccinated individuals will lead to an increase in the reproductive number and possibly the re-establishment of endemic measles and accompanying mortality. In their attempt to avoid the perceived risk associated with vaccination, parents' behavior collectively results in a substantial increase in the real risk of exposure to measles.

If you can access the paper, check out the figure - it's shocking how sharp the rise in both the frequency and size of measles outbreaks is, and how sudden the rise in reproductive number is.

Meanwhile, mumps is also

on the rise. For example, in the last couple months there have been several outbreaks of mumps in UK universities, including

Cambridge and

Oxford. College students are vulnerable because they were born in the 1980's, before the MMR vaccine was introduced in Britain. But these mumps epidemics are happening now because of the loss of herd immunity in the general population.

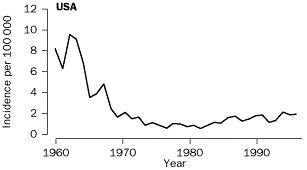

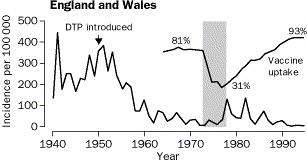

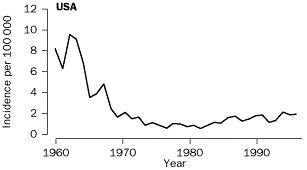

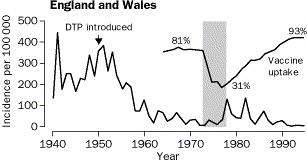

For another example of anti-vaccine movements harming public health, see

this paper, a cross-country comparison of incidence of pertussis (whooping cough), showing that countries with active anti-vaccine movements suffered increased incidence of pertussis shortly after vaccination rates dropped. This comparison is especially striking: (the gray on the England and Wales graph represents a period in the mid-1970's after a public health academic said the pertussis vaccine was not worth the risks, and before a national reassessment declared the vaccine to be of "outstanding value.")

Why do people still believe the MMR-autism link?

Why do people still believe the MMR-autism link?

Autism first becomes apparent before the age of 3 - just about the same age as childhood vaccines like MMR are given. By sheer chance, you'll always have some kids who show the first signs of autism right after they get the MMR vaccine. Parents naturally worry over their kids, especially for a condition like autism that seems to parents to rob their child's heart and soul, and the first instinct is to find an explanation. Hence the continuing tragic

personal testimonials, which unfortunately have no relevance to whether MMR really does increase the risk of autism.

The problem is that these personal testimonials really tug at the heartstrings ("Won't someone

please think of the

children! --Helen Lovejoy). And when parents are convinced that something harmed their child, they are (naturally) really, really vocal about it.

The second problem is that childhood immunization has been so spectacularly successful that it's become self-defeating in a sense. Smallpox is eradicated. No one in the developed world gets polio anymore. Measles, mumps, rubella, diptheria, pertussis - all are now extremely rare. Formerly widespread childhood diseases are now so rare that almost no one in the developed world thinks or cares about them. Because no one is afraid of these diseases anymore, people see vaccines as having a negligent marginal benefit. (Due to herd immunity, they're right - if everyone else is vaccinated, you're safe even if you're not. But if everyone thinks that way, we're in trouble.) Next to even the tiniest perceived risk, the benefits of vaccination suddenly doesn't seem worth it. This is the

availability heuristic - people think something is more likely if it's more salient in their minds. Absence of childhood diseases + media reports of an MMR scare = an availability heuristic in exactly the wrong direction.

Perceptions of science, medicine, and the establishment

I was slightly shocked by

this website, especially this bit (attacking

this article in JAMA):

The information on the internet, thank goodness, is not peer reviewed by doctors like these authors or we wouldn't be able to believe what is on the internet anymore than we are able to believe what is published in JAMA.

This sort of complete distrust in the scientific and medical establishment is the third reason that the MMR-autism link has gone so far in public opinion. It doesn't do any good to report that "the overwhelming majority of experts have concluded there is no link between the MMR vaccine and autism," because scientific "expertise" (and science itself) has lost at least some of the patina of authority it once commanded. The anti-vaccine movement is thus intimately connected (as an intellectual and social phenomenon) to

quack medicine, conspiracy theories, and even (loosely) creationism.

What to do about this? Some policy ideas do make sense - for example, the US government has a system where reporting adverse reactions to vaccines is required, and has a fund to compensate victims of the (extremely) rare complications of vaccines that stops them from suing the manufacturer. This last one stops pharmaceutical companies from halting manufacture of a critical vaccine because they're afraid of lawsuits. But these treat the symptoms of the anti-vaccine movement, not the root causes.

Meanwhile, I don't think we can turn back the clock to "just trust me, I have a white lab coat on," and a healthy distrust of "the scientific establishment" is probably a good thing, lest we end up with pseudoscientific theories like eugenics once again taking over the scientific community. In combating the excessive anti-science paranoia, I have little else to suggest other than continued efforts to explain to the public that vaccines are safe, and to do so not by appealing to expert authority but to demonstrate it transparently (e.g., publicize studies on vaccine safety). (I won't buy into the line that we need to do "more research" on vaccine safety - usually, there's plenty of research and the anti-vaccine activists just use it as a rhetorical technique, for there can never be enough research done in any field to definitively prove a negative - only to prove that the risk is lower than the very stringent limit of detection.)

Maybe the only thing that will cure us of anti-vaccine hysteria is a good old-fashioned reminder of how awful infectious diseases can be. That may be the one good thing to come out of the recent mumps outbreaks in Britain - the constant appeals to get vaccinated will be more convincing next to the actual risk of getting sick. (Availability heuristic, once again.)

There's more on this from

Respectful Insolence (scroll down to the comment by "Dreaming again" for a personal testimonial of the what vaccines are good for.)

Update: I've now posted about resistance to polio vaccine in Nigeria,

here