Anosognosia and the mind-body problem (literally)

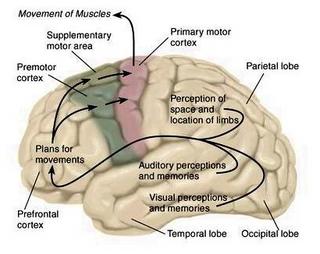

Via the NYTimes comes news of this study (Pubmed link) showing that damage to the supplementary motor cortex (see simplified diagram at bottom of post) causes a fascinating syndrome called "anosognosia" in which patients are paralyzed but persistently deny the paralysis, often coming up with elaborate confabulations to explain away why they cannot move their arm:

Dr. Anna Berti sits facing a patient whose paralyzed left arm rests in her lap next to her good right arm. "Can you raise your left arm?" Dr. Berti asks.The NYTimes does a fairly good job of explaining the theory behind why damage to the premotor cortex would create this strange perception in anosognosic patients, so I won't rehash it. (It's very interesting, so do read the article!) What I want to address is this bit:

"Yes," the patient says. The arm remains motionless. Dr. Berti tries again. "Are you raising your left arm?" she asks.

"Yes," the patient says. But the arm still does not move. ... If prodded for hours, patients will make up stories to explain their lack of action, Dr. Berti said.

One man said his motionless arm did not belong to him. When it was placed in his right visual field, he insisted it was not his. "Whose arm is it?" Dr. Berti asked.

"Yours," he said. "Are you sure?" Dr. Berti persisted. "Look here, I only have two hands."

The patient replied: "What can I say? You have three wrists. You should have three hands."

This denial, Dr. Berti said, was long thought to be purely a psychological problem. "It was a reaction to a stroke: I am paralyzed, it is so horrible, I will deny it," she said.This is a false distinction. All psychological phenomena are rooted in neurology, because the mind is the product of the brain. Now, it is meaningful to talk of some phenomena as being "higher-order" and others as "lower-order" in terms of how easily they can be explained by the biology. In this case, we could distinguish the kind of denial caused by crude brain damage (anosognosia) and the kind of denial caused by, say, a traumatic childhood (or whatever; I'm not up on my psychoanalysis). But it is not meaningful to talk of mental phenomena as if they existed in a separate plane from biological phenomena. Even denial caused by a trauamtic childhood (or whatever) would still be implemented as a neurobiological level by neurons, synapses, and so on. It is nonsensical to talk about something as being "purely" a psychological problem.

But in a new study, Dr. Berti and her colleagues have shown that denial is not a problem of the mind. Rather, it is a neurological condition that occurs when specific brain regions are knocked out by a stroke.

7 Comments:

Yes, I absolutely agree that it is useful - and, indeed, meaningful - to distinguish between different levels of explanation, some being more appropriate and useful for certain phenomena than others. That's what I meant by "Now, it is meaningful to talk of some phenomena as being "higher-order" and others as "lower-order" in terms of how easily they can be explained by the biology."

Daniel Dennett (I know I go on and on about Dennett, but he has a lot of cool ideas!) coined the phrase "greedy reductionism." We all love reductionism and it's great, but we have to be careful to be smart reductionists, not "greedy" reductionists - i.e., let's not delude ourselves that we can explain socioeconomic trends in terms of particle physics. He gives the example of a calculator - it's true that the calculator works because of a certain pattern of electron flow, but if you want a meaningful and useful explanation of how the calculator works, you have to look at the higher-order level of how the logic circuits are put together. What we "smart" reductionists want is to be able to explain each higher-order phenomenon in terms of something slightly lower-order - as you say, switching lenses as you go along.

I wanted to highlight the fundamental continuity of biology and psychology because I think it's a major conceptual blindspot a lot of people have. Many people still unconsciously subscribe to dualism, and it takes a bit of a mental shake-up to really get that the mind is "just" an emergent property of the brain. The phrase "psychological phenomenon" has to be re-framed as not being on a totally separate plane of reality, but just in a certain "region" on a scale of complexity - as a useful flag, not a reified, separate Ding an sich.

Historically, materialism has bubbled up from the lowest level - two centuries ago, people still thought that living things had a "vital force" that couldn't be explained simply in terms of chemistry. Now we know differently, even though after decades of research we still can't predict how a protein will fold from its amino acid sequence alone. I think it's the same with the neuroscience-psychology connection, just one level higher.

Glad you like the blog - I hope you come back in the future (and comment more)!

I really liked this entry... Over the past few weeks, I've been dealing with a loved one's schizophrenia diagnosis, and trust me, you really get a whole new appreciation for the biology/psychology debate when you're trying to explain things to family members. "No, he can't just 'snap out of it'"...

But I found this article interesting when they talked about the lack of insight that patients had regarding their disease...this is a symptom of other mental illnesses. Is it possible some illnesses knock out those brain regions that recognize what's 'normal' functioning? Or is it more complex than that?

Katie,

I'm glad you liked this entry! I'm sorry about your loved one's schizophrenia diagnosis; and I agree that the "can't he just snap out of it?" reaction is still sadly all too common.

I do think that awareness of normal functioning is more complex than knocking out the "awareness" brain region - for the simple reason that consciousness and awareness are not properties of the mind that can be localized to any one brain region, but rather emerge out of the interactions of all your neural circuitry.

Another example is Capgras syndrome, where patients believe that their loved ones have been replaced by look-alike strangers/robots/aliens. It's thought that this happens because the parts of the brain that mediate emotional reactions to faces is damaged, though the parts that recognize faces are not, so the patient recognizes his/her loved ones but fails to feel the expected emotional reaction - and the only apparent way to explain this strange perception is the delusion that your mother isn't "really" your mother.

I have the pleasure to visiting your site. Its informative and helpful, you may want to read about obesity and overweight health problems, losing weight, calories and "How You Can Lower Your Health Risks" at phentermine fastin adipex ionamin sibutramine Phentermine 37.5mg site.

The latter, Web 2.0, is not defined as a static architecture. Web 2.0 can be generally characterized as a common set of architecture and design patterns, which can be implemented in multiple contexts. bu sitede en saglam pornolar izlenir.The list of common patterns includes the Mashup, Collaboration-Participation, Software as a Service (SaaS), Semantic Tagging (folksonomy), and Rich User Experience (also known as Rich Internet Application) patterns among others. These are augmented with themes for software architects such as trusting your users and harnessing collective intelligence. Most Web 2.0 architecture patterns rely on Service Oriented Architecture in order to function

Thank you for sharing to us.there are many person searching about that now they will find enough resources by your post.I would like to join your blog anyway so please continue sharing with us

Post a Comment

<< Home